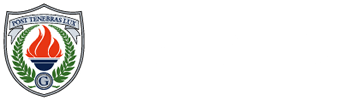

Wisdom and Eloquence: Our “Hope-Filled” Goal

By Christina Walker

Society is constantly changing; in the midst of that constant change, we are confident that “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever” (Hebrews 13:8, ESV). Rooted in his constancy, Christian educators are able to respond to the ever-changing needs around them and in their students’ lives so that they will also be able to impact society and the world for the glory of God and the advancement of his kingdom. St. Augustine and C. S. Lewis spoke of this kind of focus in terms of being heavenly minded in order to do great earthly good.

Reflecting this focus, Christian education has two “hope-filled” goals:

- helping students grow in their faith, knowledge, and relationships

- preparing them to promote this same kind of growth in their lives after graduation

In Wisdom and Eloquence, Robert Littlejohn and Charles Evans remind us that we (in the Christian tradition) receive wisdom in order to impart it, and the wisdom we pass on to the next generation is dependable—from an authority that we can trust because this authority is transcendent (p. 18). They refer us to St. Augustine of Hippo and his instructions for acquiring wisdom and becoming eloquent.

Augustine, writing in times very similar to ours (especially as Americans), offers reliable guidance for us because the methods he advocates have been tested and proven effective over many hundreds of years and, more importantly, because his driving belief is that “the Lord gives wisdom; from his mouth come knowledge and understanding; he stores up sound wisdom for the upright” (Proverbs 2:6–7). In his book On Christian Doctrine, he argues (as Littlejohn and Evans also maintain) that any learning, knowledge, or wisdom is for the sake of edifying (or loving) others and will lead to the benefit of neighbor, society, culture, and the world.

In Augustine’s writings, he asserts that the foundation for gaining wisdom is reading the Bible thoroughly and knowing what it says. Students at Geneva begin reading Bible stories in K4, and as students get older, teachers introduce them to larger portions of Scripture and go deeper into the themes that we discover in the Bible. Students memorize Bible verses and passages throughout each year from K4 through 6th grade.

- K4, K, 1st: daily Bible lessons and devotions

- 2nd: study of Genesis and Exodus (creation through the Exodus from Egypt)

- 3rd: historical and poetical books of the Old Testament (from Joshua’s leadership before entering the Promised Land to the judges of Israel to the reign of David and then Solomon)

- 4th: study of the prophets and the fall of Israel and Judah

- 5th: study of the Gospels and the life of Christ

- 6th: study of The Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles

- 7th: Old Testament survey

- 8th: New Testament survey

- 9th–12th: study of Christian thinkers, worldview, and the Bible in order to learn how to think according to the truths, traditions, and telos of the Christian faith, culminating in the class Bible in Perspective senior year

It is not only very important to everyone at Geneva that students study the Bible from K4 through senior year: it is a distinctive feature of the school.

After a thorough study of Scripture, Augustine encourages pursuing knowledge about “everything else”—studying broadly and learning about subjects that are “investigated and discovered”—building on the foundation of biblical studies. I love how Littlejohn and Evans claim that “the transcendent aim of such pursuits is to discover and to acknowledge the glory of God’s creative genius” and increase “ability to understand, function in, and positively affect the world around us” (p.19).

Never fear: Augustine does not leave us with a huge task and no direction.

As Littlejohn and Evans explain in Wisdom and Eloquence, classical education is an exceptional method for passing wisdom from one generation to another while developing eloquence because students receive “practical culture-shaping skills” through the core curriculum, and these skills equip them to learn about anything they might like to study in their present or future (p. 22). The integrated core curriculum is another distinctive feature of The Geneva School.

As we go through the book, we’ll discuss these characteristics of the Christian classical education that Geneva provides.

Certain commitments and beliefs go along with the pursuit and implementation of the liberal arts tradition:

- Being a human being means being a person of faith (what one has faith in varies wildly these days).

- To understand oneself, one must (seek to) understand the divinely ordered universe.

- People are fallen creatures, but redemption is possible.

- Truth, goodness, and beauty can be investigated and known because they are characteristics of God; pursuing these is not only valuable but achievable (even though we know our pursuit will not be perfect) (pp.25–26).

These things may seem like no-brainers to many in our community, but in today’s cultural climate, these are not things that we can take for granted. Teaching our children in this tradition cultivates in the next generation wisdom and eloquence so they can, indeed, be heavenly minded and do great earthly good. In future posts, we will explore and discuss what it means to “do great earthly good” and the many different ways Christians can embody this.